Ionic Compounds

- Ionic bonds form between a metal and a nonmetal.

- The metal is called a cation. The non-metal is called an anion.

- The cation loses electrons. This requires an input of energy.

- The anion picks up those electrons. This gives you energy back.

- The cation is now positively charged. The anion is now negatively charged.

Like magnets, the positively charged cation and the negatively charged anion will now stick together. This is called electrostatic attraction. If you still don't get this, you may want to review the sub-lesson on ionic bonding.

Now onto the goal of this lesson: learning to name ionic compounds. Ionic compounds have two kinds of names: the “proper” name (e.g., "sodium chloride") and the chemical formula (e.g., "NaCl")

Spelling It Out: The "Proper" Name

- Name the cation. This is just the name of the metal as it appears on the periodic table (e.g., "lithium").

- Name the anion. This is very similar to the name on the periodic table, only it ends in "-ide" (instead of whatever else). Here are some examples:

- Fluorine becomes fluoride.

- Chlorine becomes chloride.

- Oxygen becomes oxide.

- Sulfur becomes sulfide.

- Put them together. “Lithium fluoride.” “Magnesium oxide.” “Potassium chloride.” etc.

And that’s just about it. There are a couple more rules when you get into the transition metals, but we won't talk about those in this course.

Chemical Formulas: "Nicknames"

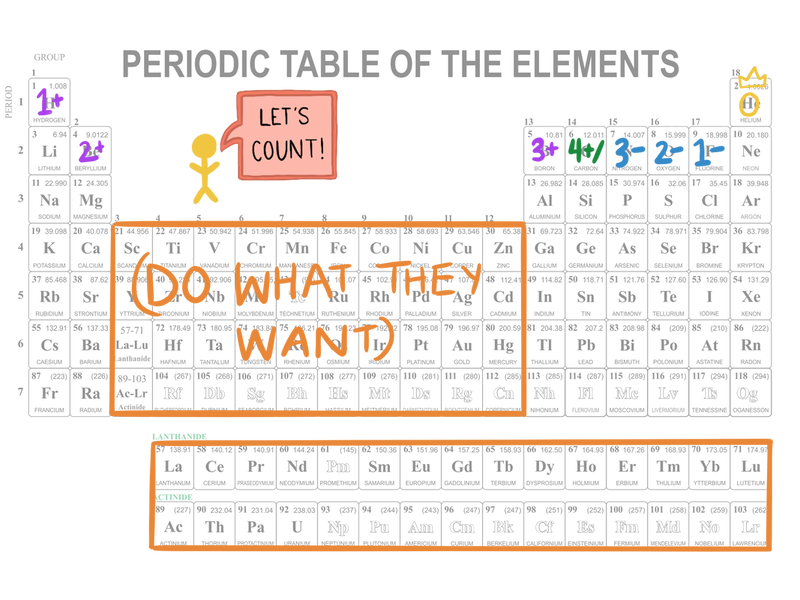

- Look at the charge. There are a couple of places you can figure this out, including your handy-dandy atomic symbols and the Periodic Table.

1 and 2 charges (i.e., 1+, 2+, 1-, and 2-) are the most common, followed by the 3's. You hardly ever get 4's (except with some of the transition metals), and when you do it's tough to say whether it'll be positive or negative. You’ll never get above 5 (again, except with some of the transition metals). This is related to the octet rule. If an atom wants to have 8 electrons in its outer shell, why would it use up a bunch of energy to ditch 5 when it could take up 3 instead?

Also note: Hydrogen is usually a 1+ charge, but sometimes it can act more like the halogens and go 1-. Oh, exceptions.

Write down the charge. This is not absolutely necessary, but you may find it useful later on.

Balance the charges (make them match). For example, in writing the chemical formula for magnesium chloride (MgCl₂), you will notice that magnesium has a 2+ charge and chlorine has a 1- charge. The sum of the charges in any given compound must add up to 0. In order to get 1- and 2+ to equal zero, you need 2 1-'s (2 times 1- equals 2-, plus 2+ equals zero). So, you're going to need 2 Cl⁻ for every one Mg²⁺. This is another one of those skills that gets to be pretty second-nature with some practice.

Write down your elemental symbols. First for the metal and then for the non-metal. Magnesium chloride to MgCl. Easy peasy.

Pride yourself on a job well done. Writing chemical formulas can be tricky at first. A bat on the back is well warranted.

Polyatomic Atoms

Polyatomic ions are covalently bonded molecules with an overall charge, which allows the entire molecule to participate in an ionic bond. For example, in calcium carbonate (CaCO3), the metal calcium is a cation in an ionic bond with carbonate (CO32-), which is an anion and a nonmetal. In ammonium nitrate, the ammonium ion (NH4+ ) is a cation (even though it isn’t a metal!) in an ionic bond with nitrate (NO3– ), which is an anion and a nonmetal.

In terms of writing chemical formulas, you follow almost the exact same procedure as for individual ions. You balance the charge for the entire polyatomic ion, just like you would for an individual ion (it may help to replace it with "X"[charge] to avoid any confusion--just remember to put the actual ion back in at the end!). When you write in the subscript, however, you must put (parentheses) around the symbol for the ion, to avoid any potential confusion. For example, you would write Mg(NO3)2, not MgNO32. You have 2 nitrates, not 32 oxygens!

Summary

- How to write the long-form name of an ionic compound, if you’re given the chemical formula.

- How to write the chemical formula of an ionic compound, if you’re given the name. This requires you to be able to find the charge of the component ions and figure out how many of each ion is needed to make the total charge add up to zero.

- How to do both of these things for ionic compounds involving a polyatomic ion. You do not need to memorize the names of any polyatomic ions for this class, but it may be helpful for you to become familiar with some of the common ones.