What is Life?

Life is the basis of biology. It is what makes Earth special relative to all the other planets that we know about. It is what makes us able to walk and talk and breathe and have thoughts. It’s also just interesting. After all, what could be more relevant to our lives than life itself? So, it is important to understand what life is and, perhaps more importantly, what it isn’t.

So, what is life? Really think about that: what is it that distinguishes something that is living from something that is not living? What distinguishes something that is not living from something that is dead?

Take a moment now to look around and identify some living things. What did you find? I’m sure you found the obvious ones: people, pets, birds flying outside your window. What about plants? Fungi? The bacteria growing on every surface around you, including your skin? Every one of these things is alive. Now go back to your definition of life: did it account for all of these different types of lifeforms? Did it exclude things that were never living, like your glass window, and things that were once living but aren’t anymore, like your wood table (wood comes from trees)?

So, what is life? Really think about that: what is it that distinguishes something that is living from something that is not living? What distinguishes something that is not living from something that is dead?

Take a moment now to look around and identify some living things. What did you find? I’m sure you found the obvious ones: people, pets, birds flying outside your window. What about plants? Fungi? The bacteria growing on every surface around you, including your skin? Every one of these things is alive. Now go back to your definition of life: did it account for all of these different types of lifeforms? Did it exclude things that were never living, like your glass window, and things that were once living but aren’t anymore, like your wood table (wood comes from trees)?

All of these things—people, trees, and bacteria—and more are alive.

This problem is one of classification. Classification is the process of sorting things into meaningful categories based on meaningful rules. We’ll learn a lot more about classification later on in this course. For now, let’s focus more on this specific problem.

I encourage you to go back and look at your definitions of living and nonliving things to try to come up with meaningful criteria that properly account for all types of living things, nonliving things, and once living things. Making a good classification system requires lots of revision and is a good skill to practice.

I encourage you to go back and look at your definitions of living and nonliving things to try to come up with meaningful criteria that properly account for all types of living things, nonliving things, and once living things. Making a good classification system requires lots of revision and is a good skill to practice.

7 Characteristics of All Living Things

Fortunately for you, you’re not the only person thinking about this problem. Today’s scientific community has come up with 7 widely accepted characteristics of living things. If something has all of these characteristics, it is living. If something does not do any one (or more) of these things, it is nonliving. If something once did all of these things but now does not do any one or more of them, it is once living (dead). Drumroll please….

Living things…

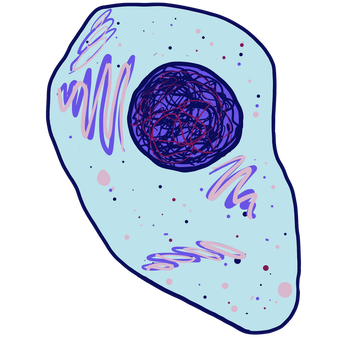

1. Are composed of one or more cells.

Cells are the building blocks of living things; more specifically, they are the smallest structural and functional unit of living things. In other words, it is the smallest thing that has all the functions of living things. They meet criteria 2-7. We’ll learn more about cells later in this unit.

1. Are composed of one or more cells.

Cells are the building blocks of living things; more specifically, they are the smallest structural and functional unit of living things. In other words, it is the smallest thing that has all the functions of living things. They meet criteria 2-7. We’ll learn more about cells later in this unit.

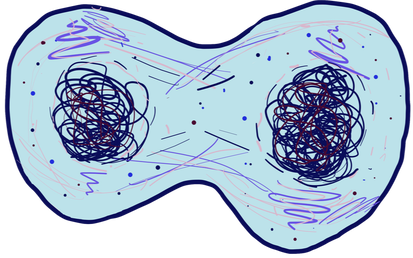

Animal cell

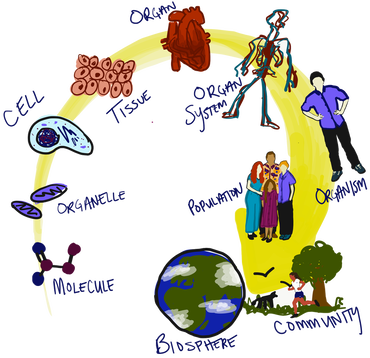

2. have different levels of organization.

These range from molecular to ecological. We’ll learn about the different levels of organization in the next sublesson.

These range from molecular to ecological. We’ll learn about the different levels of organization in the next sublesson.

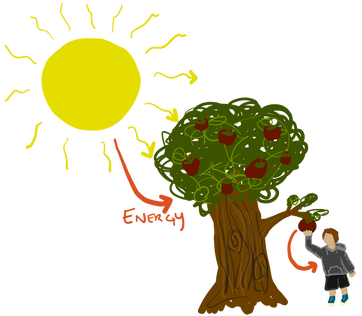

3. use energy.

In order to do stuff, living things have to get energy from somewhere. This energy source might be the sun, in the case of plants, or it might be the food/nutrients living things take up.

In order to do stuff, living things have to get energy from somewhere. This energy source might be the sun, in the case of plants, or it might be the food/nutrients living things take up.

4. grow.

Grow means “get bigger”. It is different from develop, which means “get more complex”. Growing may entail cells getting bigger, but cells can only grow to a certain size before they stop doing their job right. So, when we’re talking about multicellular organisms (that is, living things that have more than one cell—like you!), growing usually means adding more cells. This occurs by mitosis. We’ll learn more about mitosis later on this unit.

5. reproduce.

Reproduction may mean making an exact copy of yourself—this is what happens in asexual reproduction, which is a type of reproduction with only one parent (bacteria do this)—or making something very similar to yourself—this is what happens in sexual reproduction, which is a type of reproduction with two parents (most plants and animals do this). Either way, a living thing is creating a new “copy” of itself to continue the species after it dies.

5. reproduce.

Reproduction may mean making an exact copy of yourself—this is what happens in asexual reproduction, which is a type of reproduction with only one parent (bacteria do this)—or making something very similar to yourself—this is what happens in sexual reproduction, which is a type of reproduction with two parents (most plants and animals do this). Either way, a living thing is creating a new “copy” of itself to continue the species after it dies.

Cell Division

6. respond to the environment.

Things have to live somewhere, whether that somewhere is a grassy field, a barren tundra, or a trench deep in the ocean. And, that environment changes almost constantly. So, in order to live, things have to change in response to their environment, usually to keep the internal environment in the same life-sustaining state (this is called homeostasis). Responding/changing because the environment changed requires some sort of internal signalling mechanism, like molecular signalling pathways, hormones, or electrical signals (like the nervous system).

7. adapt or evolve

Adaptation is when an individual organism changes permanently (or mostly permanently) because the environment changed permanently (or mostly permanently, or because the organism moved to a different environment). For example, humans increase the number of blood cells in their body at high altitudes so they can keep getting enough oxygen (remember that air gets thinner at higher altitudes). The number of blood cells eventually goes back down when people go back to low altitudes, so that they don’t waste energy making a bunch of blood cells that they don’t really need.

Evolution is when a species changes because of a change in the environment. In evolution, the individual organism doesn’t change, but the species does because of “survival of the fittest.” Survival of the fittest means that only the organisms that are good at surviving and reproducing in an environment will reproduce to continue the species. After all, you can’t pass on your traits if you don’t make babies, and you can’t make babies if you’re dead. So, moving forward, the species only has the traits of the “fittest” parents. We’ll learn more about evolution later in this course.

7. adapt or evolve

Adaptation is when an individual organism changes permanently (or mostly permanently) because the environment changed permanently (or mostly permanently, or because the organism moved to a different environment). For example, humans increase the number of blood cells in their body at high altitudes so they can keep getting enough oxygen (remember that air gets thinner at higher altitudes). The number of blood cells eventually goes back down when people go back to low altitudes, so that they don’t waste energy making a bunch of blood cells that they don’t really need.

Evolution is when a species changes because of a change in the environment. In evolution, the individual organism doesn’t change, but the species does because of “survival of the fittest.” Survival of the fittest means that only the organisms that are good at surviving and reproducing in an environment will reproduce to continue the species. After all, you can’t pass on your traits if you don’t make babies, and you can’t make babies if you’re dead. So, moving forward, the species only has the traits of the “fittest” parents. We’ll learn more about evolution later in this course.

There are 8 species of bears across the world, each with different behavioral and physical adaptations shaped by their environment!

Other Common Traits of Living Things

Once again, something must meet all 7 of the above criteria in order to be considered living.

Those rules are the ones that pretty much everyone agrees on. Stricter standards, like these, have also been suggested (but aren’t “official”):

1. Development. As a reminder, development is different from growth. It means “getting more complex”. It changes. Growth is just a bigger version of the same thing. A toddler develops (and grows) into an adult. Bacteria grow when they swell up due to water intake. The argument can also be made that bacteria (and all species) change over time, which is the rationale for including development in the list of what makes something living.

2. Homeostasis. Homeostasis is a specific example of responding to the environment. It means keeping the internal environment stable despite changes in the external environment. For example, when you eat a lot of sugar, a hormone called insulin works to lower your blood sugar. All living things do some kind of homeostasis in the process of responding to the environment, but I didn’t include it in the main list because it’s really just an example of a broader criterion.

3. Movement. Living things don’t just stay in one spot. They move around. This may mean walking around, changing the shape of the cell to inch forward little by little (this is called ameboid movement), being propelled forward by a cellular “tail” called a flagellum, or just being swept up in flowing water.

4. Excretion. What goes in must come out (in some form or another). You eat food, you poop. You drink water, you pee. Plants convert sunlight and carbon dioxide to sugar, and they excrete oxygen (a waste product). Bacteria break down a nutrient from their environment? You’d better bet that has a byproduct, too. Living things have a metabolism, so they excrete stuff. Simple as that.

5. Intake of nutrients. This goes along with using energy. But, nutrients are more than just food for fuel. They are the vitamins, minerals, and other good stuff that are required for the chemical reactions that happen in cells to work properly. And, these nutrients have to come from somewhere.

6. Cell respiration. Cell respiration is a specific type of energy production that involves turning glucose (a specific type of sugar) into usable energy, taking in oxygen and producing carbon dioxide in the process. We’ll learn more about cell respiration later in this unit. Scientists are right to say that all living things (that we know of) do cell respiration, but others say that just because living things do produce energy in this way doesn’t mean they have to produce energy in this way to be alive—so we shouldn’t limit our definition of life.

7. Ecology. Living things live in an environment. They also do stuff. They use energy. They grow. They move. They take up nutrients. They excrete stuff. All of this doing changes the environment. This affect that organisms have on their environment is called ecology.

Here’s a great video that summarizes this definition of life:

Those rules are the ones that pretty much everyone agrees on. Stricter standards, like these, have also been suggested (but aren’t “official”):

1. Development. As a reminder, development is different from growth. It means “getting more complex”. It changes. Growth is just a bigger version of the same thing. A toddler develops (and grows) into an adult. Bacteria grow when they swell up due to water intake. The argument can also be made that bacteria (and all species) change over time, which is the rationale for including development in the list of what makes something living.

2. Homeostasis. Homeostasis is a specific example of responding to the environment. It means keeping the internal environment stable despite changes in the external environment. For example, when you eat a lot of sugar, a hormone called insulin works to lower your blood sugar. All living things do some kind of homeostasis in the process of responding to the environment, but I didn’t include it in the main list because it’s really just an example of a broader criterion.

3. Movement. Living things don’t just stay in one spot. They move around. This may mean walking around, changing the shape of the cell to inch forward little by little (this is called ameboid movement), being propelled forward by a cellular “tail” called a flagellum, or just being swept up in flowing water.

4. Excretion. What goes in must come out (in some form or another). You eat food, you poop. You drink water, you pee. Plants convert sunlight and carbon dioxide to sugar, and they excrete oxygen (a waste product). Bacteria break down a nutrient from their environment? You’d better bet that has a byproduct, too. Living things have a metabolism, so they excrete stuff. Simple as that.

5. Intake of nutrients. This goes along with using energy. But, nutrients are more than just food for fuel. They are the vitamins, minerals, and other good stuff that are required for the chemical reactions that happen in cells to work properly. And, these nutrients have to come from somewhere.

6. Cell respiration. Cell respiration is a specific type of energy production that involves turning glucose (a specific type of sugar) into usable energy, taking in oxygen and producing carbon dioxide in the process. We’ll learn more about cell respiration later in this unit. Scientists are right to say that all living things (that we know of) do cell respiration, but others say that just because living things do produce energy in this way doesn’t mean they have to produce energy in this way to be alive—so we shouldn’t limit our definition of life.

7. Ecology. Living things live in an environment. They also do stuff. They use energy. They grow. They move. They take up nutrients. They excrete stuff. All of this doing changes the environment. This affect that organisms have on their environment is called ecology.

Here’s a great video that summarizes this definition of life:

Note that many of these rules are similar to the first seven, but are just a little bit different, or are a specific type of the same thing. Other things are different but basically always accompany the original seven. For example, you’d be hard-pressed to find something that meets all of the other criteria for being alive but doesn’t influence its surrounding environment at all (ecology), or something that uses energy but doesn’t move, take up nutrients, or excrete anything. As such, when we ask you to classify things as living, nonliving, or once living in this class, we want you to focus on the first seven criteria. But, keep in mind that other criteria exist, that no classification system is perfect, and that classification systems are often and should be amenable to change.

Viruses: Not Quite Anything

There are certain things that aren’t quite alive by some standards, but aren’t quite not alive either. Viruses are the best example of this. Viruses have no metabolism. They do not produce or use energy, nor are they capable of growing on their own. But, they can hijack a cellular host (like you! Or a plant, bacterium, or virtually any other living thing) and use their host’s machinery to reproduce. They inject their genetic code into a living host, and then that host does all of that finnicky metabolism and reproduction stuff, and the virus reeps the rewards (not unlike some dude mooching off of his parents and living in their basement). Here’s a video:

So, are viruses alive? This is a challenging question, and the answer is generally viewed as: kind of, but mostly no. They don’t do anything “living” themselves, but they do all sorts of “living”-type things when they have a host.

Why do we bring this up? Well, an important thing to remember about classification is that it is a tool—our human way of trying to describe stuff so we can understand it better—not a fixed part of nature. If the classification system doesn’t describe something perfectly, we can—by general scientific consensus—change it, create a new category, or just ignore it and move on. In this case, we’ve mainly gone with “ignore it and move on.”

Summary

You should understand:

This is a great video summarizing some of the main characteristics of living things. You’ll note that their list is just a little bit different from ours (it has “maintain homeostasis” as its own category and doesn’t mention being “made of cell(s)”), but it will help you to understand some of the most important features of how we define living things:

- How to classify something as living, non-living, or once-living based on these 7 criteria:

- Made of cell(s)

- Have different levels of organization

- Use energy

- Grow

- Reproduce

- Respond to the environment

- Adapt or evolve

- That no classification scheme is perfect, including the one for living things, because the real world is more complicated than a simplified list of categories.

- That, partly because of these imperfections, other, alternate criteria for defining something as a living thing have been proposed.

This is a great video summarizing some of the main characteristics of living things. You’ll note that their list is just a little bit different from ours (it has “maintain homeostasis” as its own category and doesn’t mention being “made of cell(s)”), but it will help you to understand some of the most important features of how we define living things:

Learning Activity

Content contributors: Emma Moulton and Emily Zhang