The Octet Rule

What is Nomenclature and Why Does it Matter?

Imagine a world where there are no set languages—no rules to govern what things are called or where they belong in a sentence. Everyone just comes up with their own name for everything. Let's say a man points at a tree and says "hami oko ina gira omi na'a ah!" You respond with a cordial "iko no iko ami ari naka," and another passer by notes "helo opo noko ih." Translated from gibberish 1, gibberish 2, and gibberish 3, these could actually mean "Hey, there's a child stuck in that tree!," "I know, it's a beautiful day, right?," and "My cat just died." Or, maybe it means, "Look at what a beautiful shade of green that is!," "Yes, I love birds," and "Hey, how are you?" These people could be saying anything, and the fact of the matter is no one would ever know what was going on.

Obviously, this imaginary world creates a less-than-ideal situation for, well, everything. Who knows what would happen? As scientists, just like anyone else, we need to be able to communicate with each other. In order to do this effectively, without the mass chaos and confusion of a world with no language, an organization called the IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) has created a standardized set of rules for naming chemicals and chemical compounds. This is called chemical nomenclature. “Nomenclature” is just a fancy word for how we name stuff.

Obviously, this imaginary world creates a less-than-ideal situation for, well, everything. Who knows what would happen? As scientists, just like anyone else, we need to be able to communicate with each other. In order to do this effectively, without the mass chaos and confusion of a world with no language, an organization called the IUPAC (International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry) has created a standardized set of rules for naming chemicals and chemical compounds. This is called chemical nomenclature. “Nomenclature” is just a fancy word for how we name stuff.

The Octet Rule

We have talked about the octet rule a number of times by this point. But, just to show you how important it is, we’re going to give it a whole sub-lesson for itself. (Note: you should now be thinking, “Wow, this thing must really be important.”) And, if you haven’t taken the opportunity until now to really take it in, do it now. Never make a mistake that could have been avoided by following the octet rule. Learn the octet rule. Love the octet rule. Be the octet rule. (And know the exceptions, too!).

For most of the elements in the first three rows of the periodic table (below this, things get a little bit more complicated, but everything still wants to look like a noble gas), the “best” or most stable configuration is the one that gives the atom 8 electrons in the outer shell. They want to look just like those cool noble gases, the famed and incredibly stable celebrities of the periodic table. You can think about atoms gawking in awe at how cool noble gases are and dreaming to one day be just like them. This of course isn't technically true, but go with it. Atoms want to look like noble gases. In other words, they want to have a noble gas configuration, also called a full valence shell or an octet. (Remember: "octa-", as in "octagon" or "octet" means 8).

The exceptions: hydrogen (H), lithium (Li), and beryllium (Be) all want to look like helium (He), which is a noble gas, but only has two electrons. (In other words, they all want two electrons). It is especially important that you know hydrogen only wants 2 electrons! Boron (B) is just a weirdo. It has a full “octet” with 6 electrons.

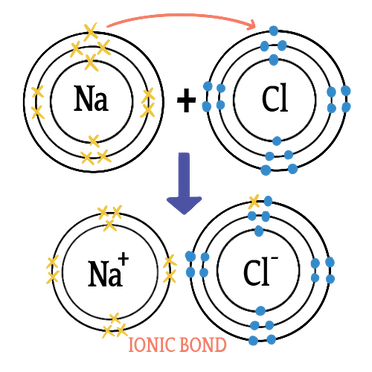

Most metals achieve a full octet by losing electrons, while most non-metals like to gain or share them. This is essentially why chemical bonding occurs: Atoms are more stable in a noble gas configuration. For example, in NaCl (that’s the formal name chemists use for table salt), sodium will lose an electron to resemble neon (10 electrons, 2 inner and 8 outer), while chlorine will gain one to resemble argon (18 electrons). Both atoms now have charges, so they attract and form a bond. You can see this process illustrated below.

For most of the elements in the first three rows of the periodic table (below this, things get a little bit more complicated, but everything still wants to look like a noble gas), the “best” or most stable configuration is the one that gives the atom 8 electrons in the outer shell. They want to look just like those cool noble gases, the famed and incredibly stable celebrities of the periodic table. You can think about atoms gawking in awe at how cool noble gases are and dreaming to one day be just like them. This of course isn't technically true, but go with it. Atoms want to look like noble gases. In other words, they want to have a noble gas configuration, also called a full valence shell or an octet. (Remember: "octa-", as in "octagon" or "octet" means 8).

The exceptions: hydrogen (H), lithium (Li), and beryllium (Be) all want to look like helium (He), which is a noble gas, but only has two electrons. (In other words, they all want two electrons). It is especially important that you know hydrogen only wants 2 electrons! Boron (B) is just a weirdo. It has a full “octet” with 6 electrons.

Most metals achieve a full octet by losing electrons, while most non-metals like to gain or share them. This is essentially why chemical bonding occurs: Atoms are more stable in a noble gas configuration. For example, in NaCl (that’s the formal name chemists use for table salt), sodium will lose an electron to resemble neon (10 electrons, 2 inner and 8 outer), while chlorine will gain one to resemble argon (18 electrons). Both atoms now have charges, so they attract and form a bond. You can see this process illustrated below.

In this model, we can see that sodium gives up an electron to chlorine, forming an ionic bond and NaCl.

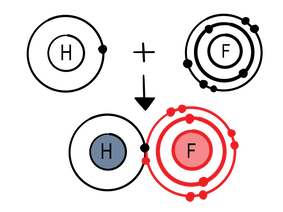

In hydrogen fluoride (HF), hydrogen and fluorine share an electron so hydrogen, which actually only owns one electron, thinks it has two electrons, like helium, and fluorine, which actually only owns seven electrons, thinks it has eight electrons, like neon.

In hydrogen fluoride (HF), hydrogen and fluorine share an electron so hydrogen, which actually only owns one electron, thinks it has two electrons, like helium, and fluorine, which actually only owns seven electrons, thinks it has eight electrons, like neon.

And that's the octet rule! Quite simple really. Internalize it. Remember it. Let it become a part of you. And, most importantly, use it!

Summary

This is mostly review. You should understand:

This is a great review video for a lot of the concepts we’ve addressed so far:

- Atoms bond in a way that makes them most stable, meaning they are lowest in energy.

- Atoms bond in a way that helps them to achieve a noble gas configuration: usually, 8 electrons. (Except hydrogen and helium, which is 2; boron, which is 6 for some reason; and stuff further down on the periodic table, starting with the transition metals, which have extra orbitals).

- Ionic bonds form between metals and nonmetals and involve electrostatic interactions of permanent, complete charges (due to donating and accepting, or “giving and receiving” electrons).

- Covalent bonds form between two nonmetals and involve sharing electrons due to wave overlap of electron orbitals.

This is a great review video for a lot of the concepts we’ve addressed so far:

Here’s another great review video:

Here it is in song:

Here it is with dogs:

Learning Activity

Content contributors: Emma Moulton and Emily Zhang